Introduction to Italian Genealogy

In its most general sense, the term genealogy refers to the study of family history, while encompassing such related fields as ethnology, onomatology and --in rather few cases-- heraldry. It is important to bear in mind that genealogy forms part of the framework of general history. The best genealogist is a competent historian, but also a good detective. While a knowledge of such topics as kinship, languages, paleography and canon law are important, the non-professional family historian cannot be expected to learn everything about these subjects. For the majority of Italian descendants embarking upon the quest for ancestral knowledge, the most important thing to know is where to obtain the necessary assistance as it is required. The purpose of this concise guide is provide you with the means to chart your course to the path of discovery of your Italian ancestors. In other words, to offer you some sound advice.

Unfortunately, Italian genealogical authors do not speak with a unified voice when it comes to research strategies, and many do not possess a genuine knowledge of Italian history --hence the redundant repetition of the Garibaldi myth and many similar misconceptions--, some of which may adversely influence the family historian's perspective. An example of this is the impression that the Italian North was always wealthier than the South, and that this economic disparity prompted millions of southerners to emigrate. In fact, Naples was the most prosperous and populous of the Italian cities until its annexation to the new Kingdom of Italy in 1860. The second wealthiest Italian city of that era was not Rome, Turin or Milan, but Palermo. It was partly because of the North's relative poverty that most Italians to emigrate before circa 1870 were from northern regions. Around that period, the artificially bolstered economy of the Kingdom of Italy began to favor the North at the expense of the South, and by 1890 most emigrants were from the South, which by then was less industrialized than the North.

History and Culture in Your Genealogy

As you begin to research your Italian roots, it is worth visiting your local bookstore and public library to obtain a few books that will aid your efforts at placing your ancestors into their proper historical context. Medieval and modern history are most important, and highly recommended. No single work is perfect, but many are worth reading. The books by Dennis Mack Smith are reliable, though they reflect some foreign biases. Sir Harold Acton authored some fine works on the Kingdom of Naples; those by Benedetto Croce on the same topic are a bit fanciful. John Julius Norwich and Steven Runciman wrote landmark works on medieval history. Giuseppe di Lampedusa's The Leopard, though fictional, provides profound insights into nineteenth-century southern Italian society. Gerre Mangione and Gay Talese have written about the Italian immigrant experience in the United States, with extensive research in Italy. Luigi Barzini's unsurpassed works on Italian attitudes are indispensable, and Claire Sterling's book on organized crime is a virtual window into the attitudes which shaped today's South. Works dealing with the Austrian Empire are invaluable to any study of Tirolean history; it is easier to learn about your ancestors' lifestyles when you know more about the region where they lived. Don't neglect local history, either. This provides information on the places where your ancestors lived, and even if your ancestors are not mentioned in a general history, they may have played a part in the history of their city or town. Accuracy in Italian genealogical research depends on many things, the most important of which is a knowledge of the Italian language. This enables you to interpret records more easily, and allows you to read Italian historical works that are not available in English translation. An evening course is an excellent way to start learning Italian. It is worth mentioning that a knowledge of regional dialects is sometimes useful, but most Italian records are written in [Tuscan] Italian and Latin. Nevertheless, regional considerations might argue your studying a language other than Italian: French for some Piedmontese records, German for certain Tirolean records, etc.

Ethnology is the comparative social science that examines such things as customs, clothing, religion, cuisine, music and language. It distinguishes Italians from Japanese, and Americans from Australians. Because "Italy" has existed as a nation state only since circa 1860, ethnological factors also serve to distinguish Tuscans from Sicilians, Lombards from Calabrians, and Sardinians from Apulians. Ethnology is what makes your Piedmontese ancestors Piedmontese, and your Sicilian ancestors Sicilian. The way your ancestors worshipped, dressed, worked, and named their children reflect ethnological characteristics. Ethnological norms help us to know the remote ancestors we could never meet. These generalities are not "stereotypes".

Yes, stereotypes certainly exist, but many of these relate to factors other than history. For example, there exists a stereotype of Italians as having dark hair and eyes, and "olive" complexions, as though blond-haired, blue-eyed Italians were anomalous. In fact, there are many Italians who have light eyes and blond or red hair --especially in the South, which in the Middle Ages was ruled by Longobards and Normans who bore these physical traits. Another frequent stereotype is the premise that all Italian immigrants in the Americas were impoverished or illiterate. While many certainly were victims of such conditions, many others were solidly middle-class (skilled craftsmen, merchants, et al.); some may have been perceived as "illiterate" simply because they couldn't read or write English. Corollary to this misperception is the stereotype of nineteenth-century Italians as landless peasants, when in fact most families owned a house and at least a small parcel of land; we know this because census and land records (known as catasti and rivelli in Italian) dating back to the sixteenth century are full of references to the land holdings of ordinary Italians.

However, in the interest of discouraging what are perceived as "negative" stereotypes of Italians, certain ethnic Italian organizations (outside Italy) prefer to foster their own notions of what constitutes "Italian" identity, and their ideas do not always reflect historical or sociological fact. The Italian monarchy, the Mafia, the Pact of Steel, and silver-haired Italian octogenarian widows dressed in black are just a few of the realities that the more outspoken members of some of these organizations would like to see banished from the Italian historical landscape. Don't let them banish genuine Italian culture from your family history project, and don't let them tell you who or what your Italian ancestors were!

Getting Started With Domestic Records

Unlike most historical disciplines genealogical research usually commences in the present and works backward toward the past. If your ancestors have lived outside Italy for a few generations, you must establish your Italian-born ancestor's precise date and place of birth or marriage in Italy if you wish to proceed to establish a lineage. Along the way, you might discover other interesting information pertaining to their settlement in a new country. However, your primary objective should be to determine accurate biographical details that will facilitate research in Italian records. You may already know where and when the Italian ancestor was born. If so, immigration information may still be interesting as family historical knowledge. Before you consult microfilmed immigration records, old census records and steamship passenger lists, question older family members regarding details of your ancestors lives in Italy. Their recollections may not be accurate in every case, but fundamental information relating to geography could save you a lot of time and effort. It is also worth knowing where an ancestor was naturalized.

Introduction to Italian Records

Since much has been written about various notary, census and military records, even if some of it is in serious error, it is necessary to clarify the extent to which the genealogist should rely upon these documents. The primary records to be consulted in Italian genealogical research are acts of birth, baptism and marriage. Acts of death, though they may be considered "primary" records, are less reliable that acts of birth and marriage; atti diversi relate to extraordinary events, such as delayed registration of births. In most southern regions (the former Kingdom of the Two Sicilies), vital statistics acts date from the early 1800s, and this is also true of certain northern localities (such as Parma). Elsewhere (in most of the former Kingdom of Sardinia, the Grand Duchy of Tuscany, the Papal States, etc.), such civil records were instituted only around 1860. Civil (vital statistics) records are invaluable; they typically include professions, approximate ages, and other information unavailable in the older primary records consulted by the genealogist-namely, parochial acts.

However, the absence of vital statistics records means that we must, in any event, rely upon parochial records for periods before circa 1800. Parochial census records (stato delle anime) rarely exist, local census records (stato di famiglia), when these exist, usually relate only to the late nineteenth century. Under most conditions, secondary records serve to provide particular details which might be lacking elsewhere, or to explain familial lifestyle (assets, professions, etc.). Secondary records (land and census assessments, military service records, heraldic-nobiliary records, notarial acts, etc.), when these exist, should be viewed as "primary records" only when the aforementioned parochial and vital statistics records do not exist, have not been preserved, or are otherwise unavailable for consultation.

Unavailable? Gaining access to parochial archives in Italy is notoriously difficult, and comparatively few such records will ever be microfilmed.. In some cases, obtaining access to these archives is a bureaucratic exercise requiring months or even years of negotiation. Inundated with postal requests for free genealogical assistance, overworked Italian pastors are reluctant to spend their time entertaining the needs of researchers, or even responding to most letters.

Certain vital statistics records have been microfilmed, and may be available to you through the auspices of the LDS Church (Mormons) via a family history center. Obviously, this presumes that you can read the records in question. Even if you can, the typical researcher must bridge the gap between the birth of an immigrant ancestor (circa 1890, for example) and the 1860s, the most recent period for which microfilmed vital statistics records are typically available. This may necessitate contacting the vital statistics office of your ancestor's home town for information that would facilitate such research. Although they are generally unwilling to conduct actual research, vital statistics officials might provide you with an extract of the act of birth (including parentage) of an ancestor if you furnish them with a precise name and date. Privacy laws preclude their issuing contemporary certificates (for persons who may still be living) to third parties.

In Italy, vital statistics and other records, for localities where these exist, may be consulted directly at a regional Archive of State, which is usually based in a provincial capital. However, you should speak some Italian if you hope to communicate with the archival staff, and you should ensure that the records of interest to you are retained at the archive in question. Remember that Italian hours and holidays differ from American ones.

Understanding Italian Records

A number of publications can assist you with research strategies and methods too detailed to be presented here. It is important that you read these critically, considering also the information acquired in other sources because, for some of the reasons described earlier, few of these publications present the degree of absolutely accurate, sound advice that applies to every Italian family history project. Moreover, each research project is unique. Information regarding historical facts of peripheral interest to genealogists is best sought in specialized works dealing with the seventeenth century, the Risorgimento (Unification Movement), and so forth. Among the misnomers in certain books on this topic are references to "Napoleonic records" and various other documents.

Transcription, Translation and Presentation

The documents you will encounter in Italian genealogical research --either in original or microfilm records-- vary by region and period. An act from a seventeeth-century Byzantine Rite Catholic baptismal register in Sicily might incorporate Greek, Latin and Sicilian elements. Most parochial records are written in Latin or Italian, and a degree of knowledge and practice is needed to render accurate transcriptions and translations.

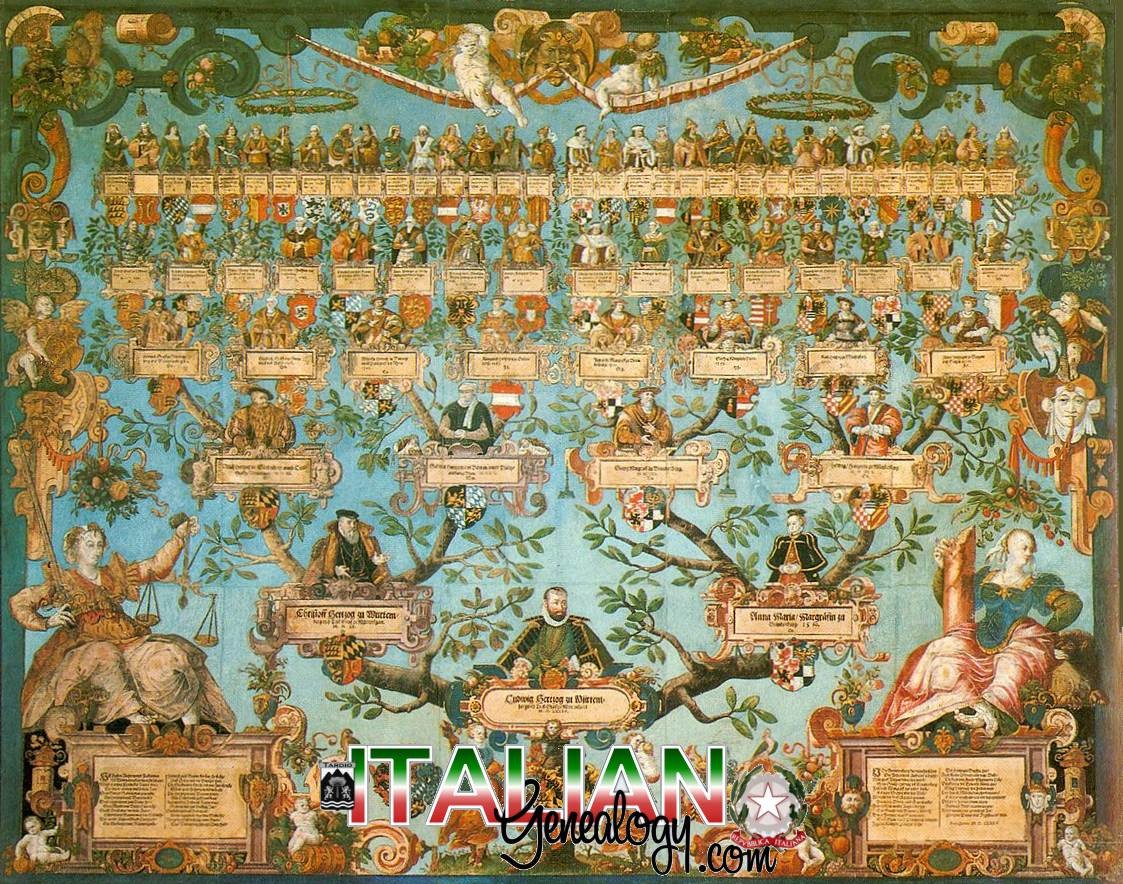

Two formats are employed in the presentation of pedigrees. The traditional agnate (patrilineal) format concentrates on lineage through your father's father's father, etc. This may include collaterals (siblings) in some generations, but except for spouses every individual indicated will be of the same family and bear the same surname. In the seize quartier (multilineal) format, preferred by many American genealogists, every ancestral lineage is indicated in each generation; in other words, the father and mother of each ancestor, ad infinitum. Patrilineal genealogies are usually more profound than multilineal ones.

Source Documents

In some cases, it is possible to obtain certificates or photocopies of supporting documents such as acts of baptism or acts of birth. Often, however, this is either impractical or impossible, especially with original records in Italian archives. Why? A photocopier may be unavailable, or photography of archival materials may not be permitted. Sometimes it is simply inconvenient for an overworked pastor or vital statistics registrar to write numerous certificates for a genealogical researcher's needs. Under such circumstances, it is best to request supporting documents for a few acts which interest you most or are most important to your project.